Issues:

Keywords:

1. The role of Non-Governmental Organisations – highly interested but without decision –making power

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been playing an important role in the UNFCCC negotiations even if only participating as observers. There are a large number of observers from NGOs, some of which have been influential in contributing to the position of parties, not only due to lobbying, but also through other means, such as representing other levels of government (e.g. city authorities), or reporting and analysing the progress in the negotiations, or acting as watchdogs.

A number of organisations, frustrated by the halting pace of the negotiations, have also become active on the ground by carrying out their own initiatives to reduce emissions. Some of these initiatives have been very successful, which has subsequently led to greater visibility and influence. This section will give an overview of the UNFCCC admitted NGOs and highlight some of the most influential ones.

1.1 The different observer organisations

Non-governmental stakeholders that are interested in following the negotiation process can request admission to attend the UNFCCC sessions as "observer organisations". There are several categories of observer organisations, including:

- Other UN agencies, such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD);

- Specialised international agencies, like the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), or the Global Environment Facility (GEF);

- Intergovernmental organisations (IGOs), such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Energy Agency (IEA), or the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB);

- And non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which are the focus of this article.

1.2 The growing number of NGO observer organisations and their constituencies

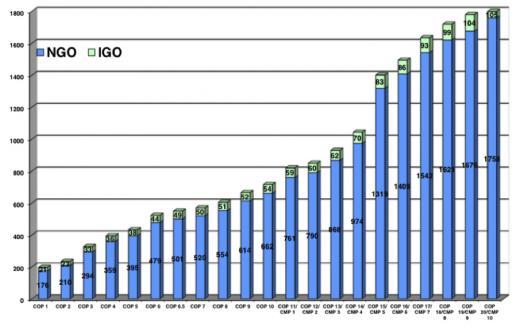

As of February 2015 the UNFCCC has admitted 1758 observer NGOs (compared with 105 IGOs) (Figure 1). The NGO category is itself subdivided into nine constituencies, which seek to group, represent and coordinate the participation of the main currently recognised stakeholder and civil society groups.

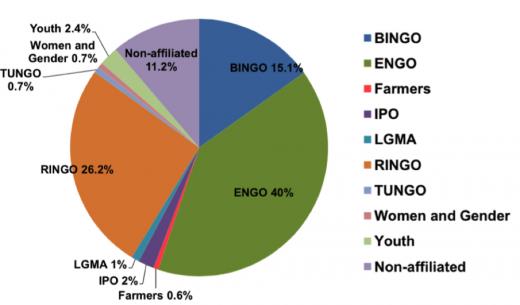

The three largest constituencies, Environmental NGOs (ENGOs), Research and Independent NGOs (RINGOs), and Business and Industry NGOs (BINGOs) group about 80% of all NGOs; each of the other groups accounts for around 2% of NGOs or less (representing local governments and municipal authorities (LGMAs), indigenous peoples organisations (IPOs), trade unions (TUNGOs), farmers, women and gender, or youth (YOUNGOs)) (see Figure 2). About 75% of the observer organisations are headquartered in Annex I countries, of which approximately a third are in the US (see UNFCCC admitted NGO database1).

The number of constituencies has increased over the years, from two initial constituencies to the present nine. The general position of the three largest groups (BINGO, ENGO and RINGO) is the following:

The BINGO2 constituency represents the business and industry sector. According to a 2014 survey by Nasiritousi, Hjerpe, Linnér3, it is perceived as being influential on decisions, agenda setting and policy-markers in particular on issues of mitigation where industry has a central role to play. According to a recent BINGO statement4, one of their key objectives is, in addition to provide technical and sectoral expertise from its members, to promote flexible market-based instruments, innovation and technology deployment. The BINGOs high profile is considered to be stemming from the important role businesses play in providing technical knowledge and sectoral expertise to negotiators. Their focal point is the International Chamber of Commerce, which has a long history in coordinating business interests in international fora. Undeniably, BINGO members also represent important economic interests for governments and are well represented, but it is important to highlight that their interests are far from homogeneous. BINGO combines a large array of companies worldwide, from large emitters to technical solutions providers, the latter having grown in importance over the years. How BINGO has evolved and balanced members' interests and its relations to the UNFCCC is carefully detailed in Tully (2007)5.

The ENGOs are the largest constituency, and represent over one thousand NGOs. The diversity of positions in the constituency has led in 2009 to an official split within the ENGO into two groups, one led by Climate Action Network (CAN) with approximately 900 member organisations and the second by Climate Justice now (CJN!) with approximately 160 members. According to a 2014 survey of UNFCCC participants6, the ENGO constituency is generally perceived as influential, but not in the same fields as the BINGOs. Their area of influence addresses primarily awareness raising and the representation of the concerned public and marginalised voices, while it is less influential as solution-providers.

The RINGO constituency7, which represents the research community and other independent organisations, seeks to inform the Parties of the availability of a large body of research, which can support the formulation of evidence-based policies. The RINGO constituency aims at providing knowledge of the physical causes and consequences of climate change, as well as of the technological and policy tools that are being researched by RINGO organisations across the world8. According to the aforementioned survey, the RINGO constituency is well perceived in its role of providing expertise, evaluate consequences and propose solutions, rather than for their influence on decision-makers6. Science supports the UNFCCC negotiations through the inputs of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCCC)9 to which a number of RINGO members, in their personal capacity, are also contributing10.

1.3 The growing heterogeneity within constituencies and its impact

The membership of NGO constituencies has risen considerably, with an ever-increasing number of organisations being granted observer status since COP 1 in Berlin in 1995, as shown in Figure 5.1. This illustrates the growing importance of the negotiations for external stakeholders, who seek either to influence their outcomes, or to get first-hand information about their progress. However, this increased participation also signifies a growing heterogeneity of opinion within the NGO constituencies. While this process may make them more representative and influential, it can also affect negatively their ability to agree on a common position.

This may lead to difficulties in presenting common positions to the UNFCCC Parties, as well as possible problems of coordination. For ENGOs, which has the largest number of members, fragmentation of opinions led to a split into two main groups, represented by two different focal points, CAN and CJN!. Divisions may arise for example out of the divergent positions on the paths to take towards decarbonisation, on the kind of actions desired by individual NGOs, or between NGOs from industrialised and developing countries on the key issue of 'common but differentiated responsibilities'. This complex situation is critically assessed by Unmüßig (2011)11, who argues that environmental NGOs often operate in isolation when attending the negotiations. Despite the divisions, Unmüßig (2011)11 considers that the role of ENGOs as watchdogs is very important, and contributes to holding governments accountable.

1.4 The particular influence of single NGOs and specific constituencies

Some individual organisations within the NGO community have become important participants. For example, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), a member of the RINGO constituency, has been providing high quality real-time reporting of the UNFCCC process in the Earth Negotiations Bulletin12. IISD provides otherwise difficult-to-follow information, due to the multiplicity of meetings happening in parallel. The Bulletin is thus a well-regarded resource for all stakeholders, be it observers or negotiators. While remaining neutral, its informative contents have helped keeping track of the ongoing negotiating process.

Within the ENGO constituency, Gulbrandsen and Andresen (2004)13 point out a few advisory environmental NGOs, whose work has influenced the negotiations positively, such as for example the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), the Foundation for International Environmental Law and Development (FIELD). WWF is also mentioned a having a more prominent position in influencing negotiators.

Some smaller constituencies hold particular influence because of their actual capacity to act on the ground. This is the case of the LGMA constituency, which represents local governments and municipal authorities. While small in size, this constituency however represents a large number of important cities carrying out ambitious programmes to reduce emissions. Due to the influence of local governments on global energy consumption and emissions, negotiators see them as key partners for action on the ground. LGMA's objective is to secure collaboration with nations, and a financial framework through which local governments’ can fund ambitious climate actions14.

1.5 Conclusions

NGOs have grown in importance in the UNFCCC process, despite the fact that they do not take part in formal decision-making. The number of admitted NGOs has grown from 176 in 1995 to 1758 in 2014 and the number of NGO constituencies from two to nine. While some constituencies and specific NGOs within the constituencies have become influential due to the quality of their participation and their role on the ground, the heterogeneity of the NGO members within the constituencies has also brought tensions, sometimes leading to difficulties on agreeing on common positions. Their role as observers nevertheless remains an important contributor to accountability.