Issues:

Sectors:

Keywords:

It is estimated that the total global climate finance flows are several hundreds of billions of US dollars per year. Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimated the annual flows at between USD 331 and 364 billion per year (2011-2013 data1 2), while the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance estimates them to be between USD 340 and 650 billion (2010-2012 data3).

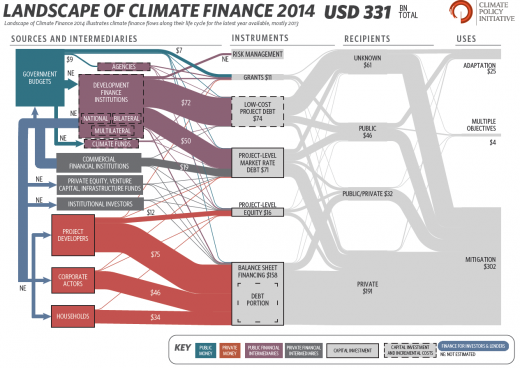

The landscape of climate finance is diverse and extensive. CPI has provided a framework for the classification of the climate finance landscape4. Climate finance flows can be classified based on several dimensions, including the sources, instruments, disbursement channels, recipients and end uses. The 2014 annual inventory of climate finance flows by CPI2, categorised on these dimensions, is illustrated in the image below. The several aspects of the image are explained in the following sections of this knowledge package. In knowledge package "Climate Finance for Reductions of Emissions and Vulnerability", background information on climate finance, its definition and principles are available.

The Standing Committee on Finance3 aggregates climate finance in two ways, being (a) the global total climate finance flows and (b) climate finance flows from developed to developing countries, also known as international climate finance. Although the majority of climate finance is from private sources, public climate finance is important to incentivise private investments and to scale-up total climate finance5.

There are great challenges in the collection, aggregation and analysis of climate finance data, as there is limited access to data, and available data are from diverse and inconsistent sources. The reliability and comprehensiveness of information on the climate finance landscape should therefore be considered with care. As introduced above, two main sources of climate finance assessment are the Global Climate Finance Landscape reports by CPI and the Biennial Assessment by the Standing Committee on Finance1 2 3. This knowledge package uses the latest CPI report6 as a main source, since this gives the most comprehensive and up-to-date overview.

1. Sources of climate finance

The diagram above classifies the sources of climate finance among four types. Public money is noted in bright blue, private money in red. Public financial intermediaries - entities that provide the market function of matching borrowers and lenders or traders - are noted in purple, and private financial intermediaries are in dark grey. Total estimated global climate finance flows in 2013 reached USD 331 billion, of which 42% was contributed by public actors (governments and intermediaries)7.

1.1 Public sources

The public sector directly contributed between USD 6 and 12 billion8. This mainly encompasses contributions by developed country ministries and government agencies, financing activities in developing countries. There is limited data about worldwide domestic public budgets for climate change, so this is not included. However, CPI estimates that domestic public climate budgets could reach "at least USD 60 billion a year"9.

1.2 Public intermediaries

The other, and main, component of public sector finance is public intermediaries. This includes climate funds as well as Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) such as National and Multilateral Development Banks (NDBs and MDBs) and Bilateral Financial Institutions (BFIs). Public intermediaries committed approximately USD 128 billion of climate finance flows. These institutions usually provide both financial support and technical assistance for project development activities in developing countries.

The main categories of public intermediaries are described below, being the Global Environment Facility (GEF), MDBs, NDBs, BFIs and climate funds.

Global Environment Facility

The GEF was established in 1991 as a partnership between United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Bank. The GEF focuses on climate change as well as biodiversity, desertification, etc. With regard to climate change, the GEF functions as an operating entity of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC10. Since its establishment, the GEF has provided USD 13.5 billion in grants and leveraged USD 65 billion in co-financing for projects in developing countries. In 2014, the GEF Council decided on the funding for the sixth funding cycle, from 2014 to 2018. Pledges by thirty donor countries totalled USD 4.43 billion11, of which between 1.22 and 1.37 billion is available for climate change mitigation.

Multilateral development banks

In addition to the World Bank, the following four large continental development banks are usually considered the main MDBs: the Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). While the original focus of the MDBs was on economic development and poverty reduction, they are now increasingly incorporating climate change into their operations. Large MDB usually have in-house expertise available, which allows them to pioneer innovative and complex financial products and analyse the risks of promising but unproven new technologies.

National development banks

NDBs are government-backed financial institutions with a specific mandate to support the improvement of financial conditions in local financial markets, by encouraging engagement of private financial intermediaries. NDBs can aggregate large numbers of small-scale projects by adopting a portfolio approach, streamlining processes and minimising transaction costs 12 13.

Bilateral financing institutions

Bilateral financing institutions (BFIs) are created and directed by national governments for the purpose of providing aid to certain developing countries, or to invest in development projects. Related to BFIs are bilateral development cooperation agencies, which often provide grants with only a development objective, while BFIs also have a profit objective14. For example, in Germany the main BFI is the KfW Group, while the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) is a bilateral development cooperation agency.

Most BFIs and cooperation agencies have in recent decades started to integrate climate finance into their development activities, and therewith they have become key sources of climate finance. Many of these BFIs have participated in the establishment of (multilateral) climate funds. For example, the BFIs of Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States participate in the CTF.

Climate funds

Multilateral and national climate funds approved around USD 2.2 billion of climate finance, and are there with a relatively small flow8. However, this relatively new source of finance is expected to increase in importance as mechanisms to transfer money from developed to developing countries. Climate funds mainly finance projects in the form of grants and low-cost debts. Some of the most important climate funds include the Climate Investment Funds, the Green Climate Fund and special funds for climate change adaptation.

- The Climate Investment Funds are two funds that are administered by the World Bank, and implemented in association with the four main continental MDBs: the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) and the Strategic Climate Fund (SCF). The funds aim to support investment programmes for the implementation of countries’ low carbon development strategies, with the SCF providing three targeted programmes on renewable energy, forests and climate resilience. Total pledged funding for the Climate Investment Funds amounts to approximately USD 7.5 billion.

- The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was designed as an operating entity of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC at the climate change conferences of 2009 -2011, in addition to the GEF. The fund is expected to become the main multilateral financing mechanism for the support of climate action in developing countries, being the centrepiece of the efforts to raise USD 100 billion of climate finance annually by 2020. The GCF has a special Private Sector Facility (PSF), which aims to encourage private investment in mitigation and adaptation projects.

- There are several climate funds that focus specifically on climate change adaptation. The main international fund, set up at the climate change conference of 2001 (COP7, Marrakech), is the Adaptation Fund (AF). The fund finances adaptation and resilience activities in developing countries that are vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change15.

- The Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) was established under the UNFCCC to meet the adaptation needs of the world’s least developed countries. The specific focus of the LDCF is the financing of the preparation and implementation of National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs).

1.3 Private sources

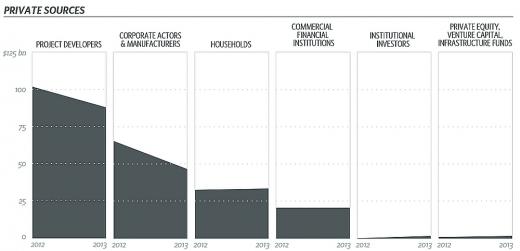

Most of the climate finance is provided by private sector actors. In 2013 private sector climate investments amounted to USD 193 billion.

Within the private sector, the largest classes of investors include energy utilities and energy project developers, corporate actors, and households, followed by several types of private intermediaries16.

Even though project developers are a very large player in climate finance, they are also major investors in high-emitting technologies such as new fossil fuel combustion plants. Therefore, it is a major challenge to shift project developers’ financial resources towards mitigation and adaptation investments.

1.4 Private intermediaries

Private intermediaries consist of commercial financial institutions, venture capital, private equity and infrastructure funds. Commercial financial institutions were the most important type of private intermediaries for climate finance in 2013, contributing USD 21 billion.

Six main barriers are identified that makes private intermediaries refrain from 'green' investments, and therefore hamper the scaling up of private climate finance17:

- Lack of economic business case: a perceived lack of investment-worthy opportunities, and perceived high risks as a result of uncertain renewable energy subsidies and volatile oil and gas prices.

- Policy uncertainty: the chances of meaningful changes to near-term climate policy are perceived to be small.

- Higher risk in developing countries: green investments in developing countries carry geopolitical risks such as corruption, political uncertainty and poor governance frameworks. In addition, investment processes are not up to developed country standards.

- Lack of a track record: track records are short and not compelling, which has resulted in a loss of confidence of investors in green investments.

- Liquidity: green growth requires significant infrastructure investments, but many funds are subject to liquidity constraints imposed by the relevant regulator.

- Investment time horizons: large corporate pension plans are ‘de-risking’, moving away from long-horizon investments such as green infrastructure.

2. Instruments

A range of economic and financial instruments exist, that can be employed by private and public investors to support mitigation and adaptation projects. The Climate Policy Initiative distinguishes five main categories of instruments18:

- Policy incentives: income-enhancing mechanisms such as feed-in tariffs and subsidies, tradable certificates, tax incentives, clean energy subsidies, etc.

- Risk management: guarantees that mitigate the risks associated with low-carbon and climate-resilient investments.

- Grants: cash transfers and in-kind support of goods and services.

- Low-cost debt: financing with better conditions than those prevailing on the market, such as lower interest rates and longer loan terms.

- Capital instruments: project-level market rate debt, project-level equity and balance sheet or sponsor-level financing.

Climate change mitigation projects are often financed with a mix of equity and loan instruments, and supported by a mix of policy incentives. Climate change adaptation projects are often supported by grants and low-cost loans18.

In the 2014 climate finance landscape report by The Climate Policy initiative, only three major categories of instruments are analysed (categories 3-5). Policy incentives and risk management are not included in the analysis due to data limitations. Grants made up approximately USD 11 billion, low-cost finance flows around USD 74 billion and the majority, USD 245 billion, was invested with the expectation of earning commercial returns, mainly as balance sheet financing19.

3. Recipients and final uses

In 2013, at least 58% of total climate finance flows was received by private actors, 14% of climate finance flows went to public recipients and 10% to public-private partnerships. For the remaining flows, approximately USD 61 billion, the recipient has not been reported. Specifically for adaptation financing, the share of public actors as recipients of climate finance was much larger, with 48% 20.

Out of the USD 331 billion of climate finance in 2013, 91% was invested in climate change mitigation. By far the largest use of climate finance investment has been renewable energy generation, with 71% of total climate finance flows. 9% has been used for energy efficiency, 12% for other mitigation measures, and 8% for climate change adaptation. There are no reliable data sources for private and domestic public adaptation interventions, as these are often integrated with development policy and business activities. As a result, activities for climate resilience are rarely reported as such21.

4. Geographic flows

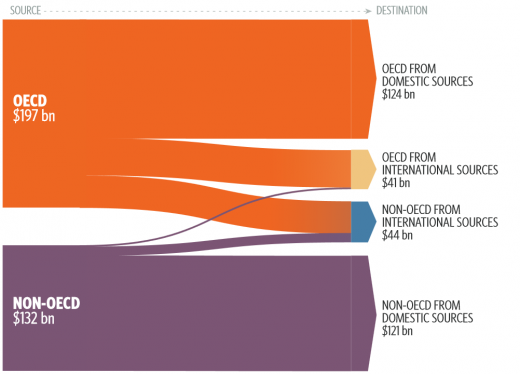

The majority of global climate finance is invested in the country where it originates. 63% of climate finance from OECD countries and 92% of climate finance from non-OECD countries flowed to domestic recipients. Considering this high share of climate finance used domestically, it follows that regions that contribute the most to climate finance also enjoy the highest levels of investment.

The Climate Policy Initiative estimates that between USD 31 and 37 billion of climate finance flowed from developed (OECD) to developing (non-OECD) countries. An estimated 94% of these flows stems from public sources. International climate finance flows from developing country sources is rarer; USD 10 billion flowed from developing countries to other developing countries (South-South cooperation), while USD 2 billion flowed from developing countries to developed countries.

East Asia and the Pacific was in 2013 the largest destination of climate finance flows, with USD 98 billion of investments, closely followed by Western Europe (USD 90 billion).

5. Leveraging private climate finance

Although the sections above have shown the scope and diversity of climate finance flows, it is recognised that this is by no means enough to stabilise global temperatures and ensure climate resilience. The private sector is acknowledged to need to play an important role in increasing finance flows, and public finance can play a role to leverage the required private finance. Leveraging is then defined as "the process by which private sector capital is mobilised as a consequence of the use of public sector finance and financial instruments" 13.

Experience of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) shows that there is great potential in leveraging climate finance for climate. One dollar of climate-related investments by MDBs can bring in around three additional dollars from other investors, on average13. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) estimates the leverage factor to be even higher. For example, for every dollar of direct equity provided by an MDB, private investors could provide eight to ten dollars23. However, there are significant variations across project types. In general, greater leverage can be achieved with well-established technologies, as it is easier to attract private financiers to participate in investment plans that are well understood.