Issues:

Keywords:

1. Mitigation requires international cooperation

Mitigation of climate change is a global challenge, as it has characteristics of a global public good. It does not matter where greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are reduced, nor by whom. Thus, there is a clear incentive for individuals as well as states to wait for others to engage in mitigation, i.e. to "free ride" on the efforts of others. International cooperation is required to discourage free riding by providing benefits to cooperating governments.

Once anthropogenic climate change had been identified as a serious problem in the late 1980s, the international community acted quickly to address it. It set up the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 and adopted the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992. The Kyoto Protocol, agreed in 1997, defined legally binding emission commitments for industrialised countries and market mechanisms for mobilising the most cost-effective mitigation options worldwide. However, negotiations for a universal follow-up mitigation regime failed in Copenhagen in 2009, leading to fears of a collapse of the United Nations (UN) based international climate policy system. In 2011, a new round of negotiations started aiming to define a new agreement applicable to all states from 2020 onwards; negotiations on this agreement shall be finalised by 2015. The characteristics of this agreement remain to be decided (see Knowledge Package: International Climate Policy: Overarching: Background: History of the UNFCCC and rough state of play (2015))

2. Uncertain climate impacts require economic "co-benefits"for mitigation efforts

A generic challenge for international mitigation policy is that actors (including governments) differ with regard to their perceptions of mitigation costs. Moreover, impacts of climate change are seen as uncertain and distant in space and time. In such a situation, economic theory predicts governments will only act unilaterally if they find mitigation justified by "co-benefits" such as health benefits due to reduction of local air pollution or improvements in energy security. Nevertheless, we have seen some mitigation action since the 1990s going beyond the level mobilised by co-benefits. Moreover, several billion US-Dollars have been transferred through the Global Environment Facility, primarily for mitigation in developing countries.

3. Competition for funds between mitigation and adaptation

Mitigation increasingly competes with adaptation for scarce international funds. After having been sidelined for a long time, adaptation is now a stand-alone pillar of the climate policy regime; However, adaptation is not discussed in detail here (see Knowledge Product International Climate Policy: Sectoral: Adaptation: Background on adaptation needs and current mechanisms (incl. Loss&damage)). Likewise, this article does not discuss issues specifically related to technology transfer and capacity building.

4. Key criteria and indicators to evaluate international mitigation policy

How should mitigation policies look like given the challenges outlined above? The IPCC suggests that assessment of international climate policy proposals should be guided by the following criteria1:

- Environmental effectiveness, i.e. its contribution to mitigation.

- Aggregate economic performance, i.e. both economic efficiency and cost effectiveness. The former means maximisation of net societal benefits, the latter minimisation of costs to reach a given mitigation target (see Knowledge Package International Climate Policy: Overarching: Scenarios: Effectiveness/Efficiency: Mitigation costs of different scenarios, trade-offs with adaptation)

- Distributional and social impacts. This captures the principle of equity highlighted in the UNFCCC.

- Institutional feasibility, i.e. whether a proposal finds sufficient support, both within and across countries.

This last criterion can be divided in the sub-criteria participation, compliance, legitimacy, and flexibility. Regarding participation, there is often a trade-off between the stringency of an approach and the degree of participation – researchers are in disagreement whether "broad and shallow" or "narrow and deep" architectures are preferable. Strict compliance mechanisms are notoriously difficult to implement when nations can "walk away" from international treaties, but transparent monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) can put peer pressure on governments to perform. Legitimacy depends on a shared perception of participants that the process and output of negotiations is fair. Agreements that perform well on effectiveness, economic performance and distributional impacts are likely to have high legitimacy. Flexibility has two sides – it can weaken an agreement but also be crucial to keep it effective under changed circumstances2.

5. Multilateral specification of country efforts – "top-down approach"

A top-down approach to an international climate policy agreement – as, for example, embodied in the Kyoto Protocol – is managed by a strong multilateral institution and based on legally binding commitments for emission reductions or finance for as many national governments as possible3. In order to be effective, a fully fledged top-down approach would ideally also apply monetary or trade sanctions in case of non-compliance. An ideal approach might also provide for specific mechanisms to advance and expand commitments, such as using clear numerical criteria to specify levels of emissions or development at which governments would take more stringent mitigation commitments. Key issues to be decided in a top down approach are the specification of commitments as well as the design of market mechanisms, the MRV system and compliance regime (see Knowledge Package International Climate Policy: Overarching: Targets: Background: Background on UN related targets - KP QELROS and new forms of actions (issues/concerns - compliance, MRV).

6. Full top-down approach lacks support among governments

A top-down approach along the main features of the Kyoto Protocol was supported by the EU in the run-up to the Copenhagen conference of 2009, but it wanted the Annex I/non-Annex I dichotomy to be overcome. However, a fully-fledged top down approach as described above currently does not have sufficient support among governments to be seriously considered for international mitigation policy. This is due to a general unwillingness to accept stringent mitigation commitments and control of their achievement by an international institution. Key developing and industrialised countries alike are wary to take legally binding emissions commitments.

7. "Bottom-up approaches" become fashionable

Given the post-2009 fatigue with top-down mitigation policies, bottom-up approaches have become more fashionable. They can take various forms inside and outside the UNFCCC. Generally, they will be based on unilateral pledges of mitigation action as well as introduction of domestic mitigation policy instruments which can subsequently be linked among various jurisdictions. Such approaches could tackle a number of specific issues, for example the unilateral and then coordinated removal of fossil fuel subsidies. “Mitigation clubs” could form that provide incentives for compliance with their declared mitigation engagement through trade-related policies, for example in the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Group of 7 (G7) or Group of 20 (G20). The Copenhagen Accord4 of 2009 is an example for a bottom-up approach. The pledges made in Copenhagen (and thereafter) take various forms, ranging from absolute targets with different base years over intensity and technology targets to sectoral mitigation activities.5

8. Inconsistency and voluntary character of pledges jeopardise effectiveness of bottom-up approaches

The key challenge with bottom-up approaches is how to generate a dynamic that leads to significant mitigation compared to a business-as-usual emissions pathway. So far, there is no empirical evidence that bottom-up approaches achieve such mitigation. The pledges under the Copenhagen Accord, for example, are not consistent with a lowest global cost mitigation path, and would likely lead to at least a 3°C warming by the end of the century.6 The inconsistency of the pledges with an emissions path respecting the internationally agreed below 2°C target has also been stressed in the annual “emissions gap” reports by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).7 (see Knowledge Package: International Climate Policy: Overarching: Targets: Post-2020 targets: Comparison of post-2020 targets in other parts of the world w. respect to the EU (type of targets, time scales).

Experience with these types of bottom-up pledging exists in domestic policy-making, where voluntary agreements between governments and industries have been used to reduce GHG emissions from the sectors in question. Research has shown that a majority of such agreements does not go beyond business as usual activities by the companies concerned, unless there is a strong regulatory threat from the government, or a cultural element that makes companies accountable to public pressure.8 This demonstrates the potential weakness of using a bottom-up approach for the international climate regime.

9. Hybrid approach: How far will the review go?

A key feature of a hybrid approach is the combination of top-down and bottom-up elements. Already during the negotiations of the UNFCCC, a “pledge and review” system was proposed by Japan and the United States but did not find agreement in the UNFCCC or Kyoto Protocol negotiations. After the Copenhagen failure, this idea was resuscitated and is likely to inform the design of the 2015 agreement9. Key aspects of a hybrid approach could be the competence of a multilateral institution regarding the review of the mitigation proposals made by governments. If the review is just a “rubber-stamping”, we essentially have a bottom-up system. If however, the review leads to a public evaluation, this could have consequences, at the very least by providing transparency that is akin to a “naming and shaming” of governments with a weak proposed mitigation pledge. Resulting international pressure could lead to an enhanced pledge. Combined with strong MRV and credible accounting procedures, such a system would be closer to a top-down approach. The only remaining difference would be that the commitments are not negotiated simultaneously as would be the case in a pure top down system.

10. MRV and markets to enhance effectiveness

A robust hybrid system thus requires a highly transparent MRV system that, based on comparable rules for pledge formulation, can easily highlight differences in stringency of mitigation pledges and identify potential non-compliance of parties with their commitments at an early point in time. This requires agreement on common approaches to calculate baseline emissions.

Ideally, a hybrid approach would include also market mechanisms to prevent that mitigation is only done in countries that have made pledges and the system becomes inefficient due to persisting differences in mitigation costs. This, however, requires that the market mechanisms do not lead to a dilution of mitigation action.

11. Where should the regime stand?

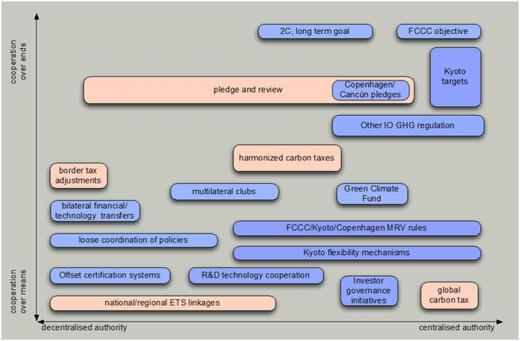

Having shown the key approaches that are under discussion for international mitigation policy, this section now assesses the whole range of approaches from full top down to complete bottom up. Figure 1 shows various international mitigation approaches according to their degree of centralisation as well as whether they address mitigation commitments or policies that eventually lead to mitigation. It shows that one approach can have significantly differing degrees of centralisation depending on its exact design. Blue elements denote existing approaches, pink elements those proposed onesin the policy literature.

12. Conclusion – if political will fails, neither top-down nor bottom-up nor hybrid regimes are sufficient

While many governments and non-governmental stakeholders have been criticising the UNFCCC process for being slow and not achieving a significant outcome, it nevertheless remains the approach with the highest degree of legitimacy – a "one eyed among the blind". Thus, a pure bottom-up approach outside the UNFCCC is as of 2015 inconceivable; it might, however, gain support if the UNFCCC process is unable to generate an agreement in 2015.

The chances of a hybrid approach to perform strongly depend on the ability of a common MRV system to make pledges comparable, to generate public pressure on laggards and trigger a “ratcheting up” of commitments. Commitments that clearly go beyond business-as-usual could then speed up low carbon technology innovation and deployment and possibly resuscitate global carbon markets - and thus facilitate further mitigation worldwide. The key ingredient for this to happen is the political will to invest in mitigation in a critical mass of countries. While national mitigation action is happening in many countries around the world, it is not clear in the political and economic climate of 2015 whether governments will feel empowered to translate those activities into commitments at the UN level that would be sufficiently ambitious to achieve that. It seems therefore important for any future regime to leave the door open for improvements over what countries are able to agree to in 2015.