Issues:

Sectors:

Keywords:

1. How countries negotiate: sovereign states and like-minded groups

Since the early 1990s, international climate policy negotiations have taken place within the context of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), with participation of almost all countries in the world. As Parties to the UNFCCC, countries act as sovereign states and in the tradition of decision-making by consensus generally all votes count. However, climate negotiations have also shown that it is often difficult to reach agreement among countries.

There are several reasons for that1. First, countries are economically, socially and environmentally diverse. Their financial capacity to respond to climate change impacts or to act on mitigation differs as well as the degree to which countries feel responsible for climate change. Second, countries may play 'negotiation games' in an attempt to arrive at a more favorable negotiation outcome for them, possibly at the expense of others. Third, climate negotiations have long been hampered by lack of scientific insights on global warming and whether and how people influence climate systems. As a result, rather than negotiations being guided by a clear problem statement and goals, formulating climate goals has long been a topic of negotiations itself.

According to the UN tradition2, Parties, while they are each represented by national delegations, are grouped according to their regions, mainly for administrative reasons:

- African States,

- Asian States,

- Eastern European States,

- Latin American and the Caribbean States, and

- Western European and Other States (e.g., including EU, Australia, Norway, Switzerland and USA).

In order to have their substantive interests better presented at negotiations, Parties usually organise themselves in 'like-minded' groups. The main groups are:

- Group of 77 (G-77), which was founded in 1964 and has nowadays over 130 developing country members; China generally collaborates with G-77 so that the group's inputs to the COP are usually tabled as G-77&China submissions,

- Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which is a coalition of 43 low-lying and small island countries (which are mostly also member of the G77&China group),

- Least Developed Countries (LDC), which contains 50 countries and which share a common interest in, e.g., vulnerability and adaptation to climate change,

- European Union (EU), which as a regional economic integration organisation has become a Party to the UNFCCC itself,

- Umbrella Group, which is a loose coalition of non-EU developed countries, and

- Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), which comprises Mexico, Liechtenstein, Monaco, the Republic of Korea and Switzerland.

In addition, there are several other groups, such as OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries), CACAM (Central Asia, Caucasus and Moldova), BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China), and COMIFAC (Central African Forestry Commission).

2. What determines the negotiation positions of countries as UNFCCC Parties?

Ideally, negotiations are supported by a clear identification and description of the (environmental) problem to be addressed with corresponding goals3. This helps countries assess whether and to what extent the course of a negotiation process is in line with the upfront goal(s). Countries then agree on forming an international coalition to implement a pathway towards the goal(s) and with clear descriptions of each country’s responsibility in the negotiated package1.

However, such an ideal situation has been difficult to realise in climate negotiations. Early projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)4 indicated how climate change and corresponding climatic impacts may occur due to increasing GHG emissions, but these scenarios were surrounded by several uncertainties. Only since the Cancun Agreements of 2010, there has been a clearly formulated longer term political goal, based on science, of limiting global average temperature increases to 2°C5.

A second reason why climate policy negotiations have deviated from an ‘ideal’ negotiation pathway is related to game-theoretical aspects. Investing in GHG emission reductions may well require economic restructuring with accompanying socio-economic costs and addressing questions such as: what would such a restructuring look like, how to balance short-term socio-economic costs with possible longer-term benefits,6 how would it affect a country’s competitiveness and whose further interests are negatively or positively affected7?

Most countries will generate different answers to these questions due to their different short-, medium- to longer-term development priorities, welfare levels, and perception of the urgency of the climate change issue. Moreover, countries may be reluctant to agree on GHG emission reductions8:

- If it feels that it could benefit from measures taken by other countries, instead of investing in climate actions itself (free rider behavior).

- If it feels that its actions are not or insufficiently met with comparable actions by other countries.

3. Polarised Positions Impede Commitment

These climate negotiation characteristics and polarised positions of the negotiating parties have complicated the introduction of legally binding commitments with strong enforcement mechanisms for all countries. For instance, although the Kyoto Protocol contained legally binding quantified commitments, these were only formulated for developed country Parties, of which the USA refused to ratify the protocol (in 2001) and Canada refused to comply with its commitments (in 2011). Moreover, as the Protocol did not set out mitigation commitments for any developing countries, it did not address the growing emissions of rapidly industrialising developing countries.

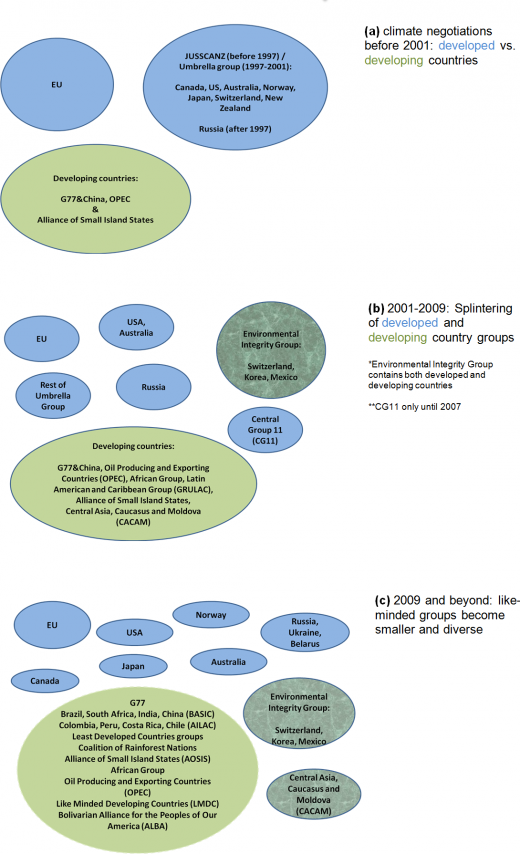

Within the context of negotiations on the Durban Platform (2011), some developing countries have expressed the view that no nation should be fully exempted from climate mitigation responsibilities. Thus the hitherto solid block of G77 developing countries has increasingly split up into smaller groups, which has also softened the usual strict distinction between developed and developing country Parties. Also the positions of developed countries have evolved. Source (see Figure 1a and b). Over time, the Umbrella Group divided into separate positions. In addition, while the EU is in principle a single player (negotiation Party), the positions of EU Member States are not unanimous.

As a result, some negotiation groups now include both developed and developing countries. An example of that is the Environmental Integrity Group, which emerged in 2001, and which includes developed and developing countries that have agreed to undertake ambitious mitigation policies.

One possible implication of this development towards a softer distinction between developed and (rapidly growing) developing countries can be that negotiations can focus more strongly on limiting or reducing GHG emissions of major emitting countries, including a number of developing countries. Nevertheless, despite these developments, developing countries continue to underline at negotiations9 the importance, in their view, of the UNFCCC principle of common but differentiated responsibilities10.

The evolution of positions and country groupings since the start of the negotiations is visualized in the six images of Figure 1.

4. Fragmentation as Progress

After the failure to reach a global agreement at the Copenhagen UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP 15) in 2009, the fragmentation of positions increased (see Figure 1c). While this may seem cause for concern, this fragmentation can in fact be attributed to actual progress in the negotiations, as well as to the increasing number of issues under discussion, such as finance, inclusion or exclusion of sectors, the definition of developing countries’ responsibilities, etc. As negotiations become more complex, the fragmentation of positions does not therefore necessarily reflect a lack of commitment by the participants.

The Paris COP in 2015 (COP 21) is expected to introduce a number of commitments with flexible approaches to accommodate the rising diversity. Despite divergent internal interpretations of the CBDR principle, or of the importance of adaptation, the G77 group will still remain influential. If it manages to reach a common compromise position on the CBDR principle, this could indeed help in reaching a substantial agreement between the parties at the COP.