Issues:

Keywords:

This Knowledge Package is the follow-up of the "History of the UN climate negotiations – Part 1 – from the 1980’s to 2010". This Knowledge Package covers explicitly the period from 2011 to 2015. Prior to COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, the climate negotiations followed a top-down approach, with binding mitigation commitments limited to industrialised countries. The events that led to the Copenhagen Accord brought an end to the top-down approach and started a new process in which countries pledged self-determined targets. This initially rather disorganised approach led to a period of uncertainty and scepticism, especially due to the fact that the sum of the pledges was far from reaching the emission reductions needed to avoid global warming beyond the 2 °C target. Nevertheless, over the years the more flexible approach is being integrated into more formal processes of transparency and control, increasing trust, and the willingness of all Parties to contribute. The new form of negotiations is leading to promising prospects for a more inclusive and effective agreement for COP 21 in Paris.

1. 2011: Durban COP re-launches efforts towards a binding legal agreement

Durban's COP 17, which took place in December 2011, marked a renewed effort to plan for a legal agreement "applicable to all Parties" (by Decision 1/CP.17), to be adopted in Paris in 2015 and to be implemented from 2020 onwards. To this end, the COP launched a new platform of negotiations under the Convention, the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP), which is composed of two workstreams.

Workstream 1 focuses on the 2015 agreement and it set interim steps, such as a draft negotiating text no later than December 2014 at COP 20 in Lima, with the aim to making available a negotiating text by May 2015. The text is to include the work "inter alia, on mitigation, adaptation, finance, technology development and transfer, capacity-building and transparency of action and support" (by Decision 1/CP.19).

Workstream 2 on the other hand, concentrates on emission reductions before 2020, with a focus on exploring possible options to reduce the large gap between Parties' mitigation pledges and the pathways consistent with limiting the increase of global average temperature below 2 °C or 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. The UNEP Emissions Gap Report (2013)1 warned that additional reductions are needed in the range of 8 to 12 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2020. The objective of Workstream 2 is to explore "opportunities for actions with high mitigation potential, including those with adaptation and sustainable development co-benefits, … scalable and replicable, with a view to promoting voluntary cooperation … in accordance with nationally defined development priorities".2

2. 2012: Doha COP agrees on rules for the Kyoto Protocol second commitment period

As an interim measure until the new agreement is expected to enter into force in 2020, COP 18 in Doha (2012) launched a new commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol (known as KP2) from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2020, and included a number of amendments to several articles of the KP. For this second period, Annex 1 Parties have committed to reduce GHG emissions by at least 18 percent below 1990 levels. However, not all countries included in the first round of the Kyoto Protocol decided to commit under KP: Japan, New Zealand and Russia opted out, and the remaining countries (including the EU, Australia, Switzerland, and Norway) jointly contribute no more than 15% of global emissions. Other industrialised countries are absent from KP2, namely the US, which did not ratify the first phase of the Kyoto Protocol, and Canada, which withdrew in 2012. Despite its limitations, KP2 was deemed to be a success, as it kept the only legally binding instrument under the UNFCC alive. As a signal to those who had decided to stay out of KP2, negotiators agreed to limit the eligibility of non-KP2 Parties to the Kyoto Protocol’s flexible mechanisms.

Other issues addressed in Doha, such as transparency, adaptation, forests, made only incremental progress, while the key issue of climate finance remained a core matter of contention between developing and industrialised countries. The latter, mainly on account of the difficult economic conditions, made no collective mid-term commitment on scaled-up funding, with only a few European countries individually pledging increased finance.3

3. IPCC Fifth Assessment warns of worsening climate

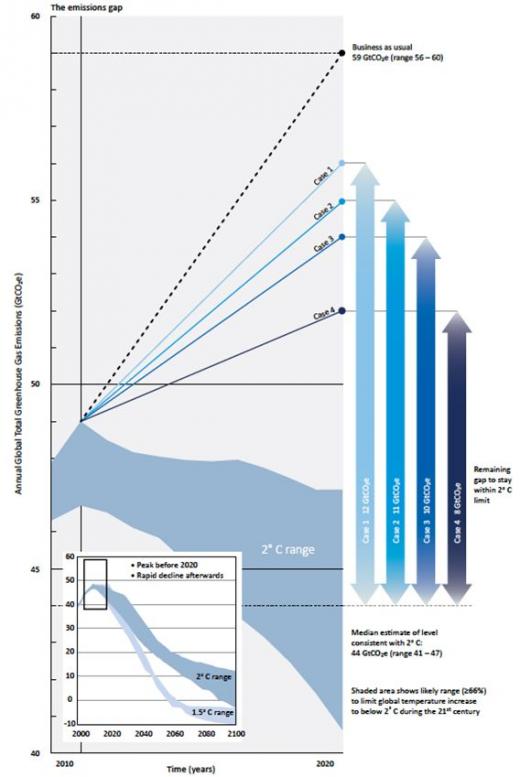

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) published in 2013 prior to COP 19 in Warsaw, presented evidence that emission trends and estimates of the effects of existing and proposed policies still lead to a potential average global temperature increase of 4°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Even if Parties fully implemented their pledges, the temperature increase was estimated to reach 3.3°C4. The higher estimate takes into account the pattern of continuous consumption of fossil fuel energy in the past decade. Even under the most stringent implementation of the pledges, a gap of 8 Giga tons carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) will remain. Figure 1 shows the different scenarios:

- Under business-as-usual (BAU), the gap would be 14 GtCO2e/yr;

- Under different cases of country pledges, the gap would be between 8 and13 GtCO2e/yr (cases 1 to 4);

- Under the most ambitious scenario, the gap would be 8 GtCO2e/yr.

The so-called "ambition gap" has become one of the core topics of the negotiations, with the objective to close this gap by 2020. Technical options are available to narrow this gap5, but success depends on the political will to implement actions beyond the existing pledges. The technical potential for emission reductions by 2020 is estimated by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) to be around 17+/-3 GtCO2e at marginal costs below US$ 50-100/tCO2e6, comfortably above the reductions needed to reach the 2°C range.

Figure 1: The amount of total Greenhouse Gas Emissions leads to different possible scenarios of global warming

4. 2013: Stalling Warsaw negotiations

Despite the concerns raised by the IPCC report the advances in the Warsaw COP 19 negotiations in November 2013 were meagre in contents and raised concerns about the Parties’ determination to reach a legally binding agreement. Nevertheless, some limited progress was made, for example in the areas of monitoring, reporting and verification for domestic action, as well as adaptation. The Warsaw COP also established the new Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts, to address cases such as extreme and slow onset events in vulnerable developing countries. In addition, it agreed on the rulebook for deforestation and forest degradation. Finally and importantly, a timeline for the development of the 2015 agreement was advanced.7

The Warsaw COP did, nevertheless, bring one important additional change, which has considerably altered the process of the negotiations. A consensus was reached that countries would submit their emission reduction pledges as 'intended nationally determined commitments' (INDCs), and that international rules would ensure transparency and appropriate monitoring mechanisms on implementation. The term "contribution" was introduced as a compromise of the terms "commitment", to describe the proposed efforts of both developed and developing countries.8 INDCs will be submitted "without prejudice to the legal nature of the contributions"9 allowing for the differentiation under the "Common but Differentiated Capabilities" principle10. This compromise cleared the way for more substantial advances in Lima and Paris.

5. 2014: Lima negotiations bring a breakthrough

Expectations for COP 20 in Lima were mixed due to the experience in Warsaw. Towards the goal of reaching a global legally binding agreement in Paris in December 2015, Lima needed to deliver solid groundwork.

Important decisions were taken in Lima to prepare the ground for a legally binding agreement. One of the most important ones has been the incorporation of a first partial draft agreement text for COP 21 in the final declaration11, which allows the Parties to start negotiating in preparation of the Paris conference. In addition the Lima negotiations led to important additional decisions:

- Adaptation was recognised to have the same importance as mitigation, in line with the demands of developing countries;

- A formal recognition of the National Adaptation Plans as a way to deliver resilience with visibility tools and linking them to the Green Climate Fund (GCF). The GCF contributions crossed for the first time the 10 billion US$ mark, including contributions from five developing countries;

- Countries reached a new level of understanding on monitoring and verification measures on the delivery of their contributions (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions or INDCs) to climate change mitigation.

The Lima outcome still left many areas to resolve. The negotiations did not address the contributions of different states in terms of emission reductions. However, based on the initial text from Lima, the ADP Workstream 1 succeeded in producing at the climate talks in Geneva a full 86-page-long draft negotiating text as a basis for the Paris negotiations, meaning a much more comprehensive document than the Lima draft12.

6. 2015: Paris: The first truly global international climate change agreement

6.1 An inclusive process

In order not to repeat the procedural mistakes made in Copenhagen in 2009, the main focus of the French COP Presidency was on ensuring that the process towards the agreement was inclusive, by listening to all views and preserving transparency. It sought compromise amongst parties, while aiming at an ambitious agreement.

At the end of the two weeks, the French Presidency was praised for having succeeded in giving ownership of the process to the Parties, making it a truly multilateral agreement. The Paris Agreement has thus succeeded in bringing 195 nations under one framework and in organising the process into a logic of global decarbonisation.

6.2 The Paris Agreement: Why it is deemed a success

The Paris Agreement not only sets a target of limiting a global temperature increase to "well below 2°C", but acknowledges the need to aim for a limit of 1.5°C, taking therefore into account the needs of the most vulnerable island nations.

It succeeded in achieving the largest possible participation by introducing enough flexibility to bring all Parties on board, but at the same time maintains several aspects of the agreement as legally binding, especially where process is concerned.

In the words of French COP President Laurent Fabius, the Paris Agreement succeeded in "being differentiated, fair, durable, dynamic, balanced and legally binding". It sought to address the needs of all countries, from the most vulnerable island countries to fossil fuel countries in need of diversification, and in general sets up a framework to aid countries in gradually building low-carbon economies.

The Paris Agreement encapsulates a logic of reduction, with several phases of first reducing the increase, then peaking and declining, with a final objective of eventually phasing out fossil fuels, and to balance all anthropogenic emissions with "removal by sinks", i.e. to achieve full carbon neutrality. Most importantly, the language of the agreement sends a clear signal for decarbonisation to policy makers, investors and the business community.

6.3 The main elements of the Paris Agreement

From a general legal perspective, the Paris Agreement has introduced a dual system consisting of i) a legally binding part that establishes a common process to ensure transparency and regular assessment of the progress achieved, while ii) leaving to each Party the flexibility to establish its targets and modes of implementation, such as for example the NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions, which were called INDCs or Intended Nationally Determined Contributions prior to the Paris Agreement). The Agreement also moves away from the strict Kyoto Protocol distinction between Annex I and non-Annex I countries, towards a more flexible differentiation between developed and developing countries, which allows for common rules while respecting countries’ different national circumstances and capabilities. The NDCs, by allowing Parties to set their own targets create de facto a system of "self-differentiation", while different articles bring detail to the differentiation, such as for example in the case of financial support13.

The other main elements of the agreement are:

- As said above, a strengthening of the ambition of the long-term goal, limiting global temperature increase by the end the century to 1.5°C compared to the original 2°C. The text specifies the objective as one of "(h)olding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C" (Article 2.1(a)). Article 4.1 also introduces the objective to achieve net zero emissions in the second half of the century.

- As the sum of the present NDCs does not allow to reach the objective of limiting global average temperature to well below 2°C, the text introduces instruments to ratchet up national ambition trough provisions on transparency and regular reporting. While there are no legally binding targets for individual countries, the monitoring and reporting process is binding. Governments will need to update their NDCs targets and measures every five years and these have to be at least as ambitious as the preceding one.

- A binding system in Article 14 of tracking progress towards the global long-term goal and the individual country goals through two different mechanisms: i) "stock-taking", which will take place every five years (the first to take place in 2023 or 2024) and where countries will announce how they have reduced their emissions; and ii) "ratcheting", whereby countries will announce more ambitious reductions, every five to ten years. A first stocktake is also meant to take place in 2018, under the form of a "facilitative dialogue" (item 20 of the accompanying Paris decision)

- A process that is facilitative rather than punitive: Developing countries will be supported to implement their contributions, while there will be no sanctions for countries not fulfilling their commitments, but the structured regular process is expected to introduce peer pressure for countries to perform.

- On finance the joint mobilisation of US$100 billion per year for mitigation and adaptation has been extended to 2025, not in the Agreement itself, but in the Paris decision. It urges developed countries to scale up their financial support. The agreement identifies the Global Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the entities entrusted with the operation of the Financial Mechanism of the Convention, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), administered by the GEF, as the key delivery instruments. For adaptation, the Agreement identifies the Adaptation Fund as an instrument. However, the text does not mention if the funding is grants or private funding. The text allows for a variety of funding for reaching this objective.

- The agreement brought back to life the notion of carbon markets, by establishing a mechanism of "Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes" (ITMOs) with the objective to deliver an "overall mitigation impact", or in other words a net-mitigation impact. This was introduced to correct the shortcomings of the CDM, where a net mitigation impact was not expected. The development of the mention of market-based approaches from just a couple of paragraphs in the ADP draft text to a full Article in the Paris Agreement is significant, and opens the way for more focused work on the modalities and procedures of the mechanism during the next meetings of the Parties. According to the provisions of the agreement, countries will continue to design, test and implement their own market-based domestic carbon pricing initiatives. Those, however, need to be then adapted to be traded as ITMOs. Impacts need to be comparable with the climate actions of other countries under the rules established in the sustainable development mechanism.

6.4 The Paris Agreement put to the test: How will it be implemented?

While the Paris Agreement has been generally praised for setting in motion the right approach, increasing the ambition level, and being truly multilateral, many challenges on core aspects of the implementation remain unclear. It is implementation that will ultimately tell us whether the Paris agreement is fit for purpose. All Parties, with the support of civil society and the business sector, will need to translate this agreement into concrete actions. The most important concern is that the current NDCs are largely inadequate to reach the 1,5% target. National emission reduction targets will need to be stepped up, while financial contributions, in particular for adaptation in vulnerable countries will need to be delivered in a predictable manner.

The agreements lack clarity on the mechanisms of implementation, with many aspects and technical work left to be fine-tuned in the Marrakesh 2016 COP 22 meeting.